Symphony No. 8 in E flat major "Symphony of a Thousand"

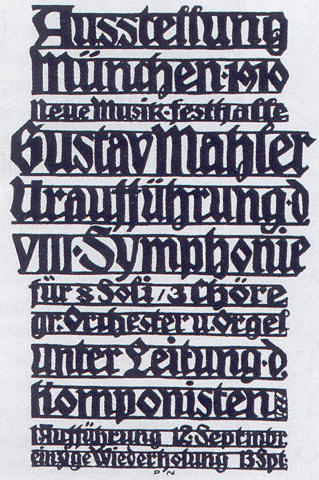

First performance on September 12, 1910 in Munich conducted by Gustav Mahler

- Hymnus: Veni, creator spiritus

- Schluss-Szene: Faust

It is the greatest thing I have as yet done. And so strange both in content and form, that it is really not possible to write about it. Imagine that the whole universe begins to sound in tone. The result is not merely human voices singing, but a vision of planets and suns coursing about. (Gustav Mahler in a letter to Willem Mengelberg, August 18, 1906)

In June 1906, one of Mahler's happiest years, Alma and Gustav came to their cottage in Maiernigg. As most of the times, Mahler feared the summer would pass without him being able to compose. One morning, however, a Creating Spirit, the "Creator spiritus", seized him forcefully and did not leave him for the next eight weeks. Within this period, he created this incredible opus without interruption as if he were in a fever. The full orchestration and completion of the partition was done in summer 1907.

The partition for the voices was published in April 1910; on September 12, 1910, the first performance took place in the Neue Musikfesthalle in Munich, followed by a second performance the following evening. Besides eight solo singers, two large mixed choirs and a boy's choir, an extended symphony orchestra is required. On the first performance, the choirs consisted of about 850 male and female singers, and the number of musicians in the orchestra was increased to 170 players; altogether, a number of 1,030 participants has been reported. This number had also been published when announcing the performances so that was where the symphony got its title from but Mahler himself was supposed to refuse it. Many political, industrial and cultural celebrities were amongst the audience, e. g. Georges Clémenceau, Stefan Zweig, Thomas Mann, Siegfried Wagner, Leopold Stokowsky, Arnold Schönberg, Anton Webern and Richard Strauss. Eight months only before Mahler's death, the performances were his greatest success and a highlight of European culture, shortly before the end of the Belle Epoque and the beginning of the darkest era in Europe's history.

The publication of the complete partition, with the revisions and corrections made after the first two performances, followed in January 1911 (without mention of tonality) dedicated "To my beloved wife, Alma Mahler". The Mahlers passed in fact through a serious crisis because of Alma's liaison with Walter Gropius; perhaps this was just the reason for this dedication.

Mahler spoke about strange form and contents, but looking closely, the form is not that strange. If, at first sight, it may appear unusual that a symphony is almost entirely sung, Mahler's artistic work proves that in his opinion, the human voice is one of the most beautiful instruments which he did use not only in his many Lieder, but also in the Second, the Third and the Fourth symphony. It is not either a Mahlerian invention to integrate the song in the symphonic writing - to think only of the final chorus in Beethoven's Ninth. If there is something unexpected, then it is rather the prevalence of the choruses and the soloists who seem sometimes degrading the orchestra to a simple role of accompanyist. But it is probably a first impression appearing false when looking at it more closely: In the Eighth, song and orchestra merge to a perfect unity, and the rare moments when one hears the solo chorus or orchestra do not change at all this over-all impression.

To the question posed again and again whether it is a symphony at all, Kralik answers with a resolute 'Yes':

For him [Mahler], the term of symphony did not simply mean the musical form which had been developed in several centuries of evolution; the symphony seemed to him - formally and spiritually - the most adapted receptacle to collect its musical aspirations towards the general, universal, the cosmic one. If the question had ever been asked, he would vigorously have refused any limitation according to which this receptacle tolerated only instrumental music at most accompanied by a bit of singing. In the symphony he saw an ideal spiritual recapitulation […].

Kralik and others are moreover of the opinion that it is indeed a symphony, even on the formal level: The first part, which was in the beginning the first of a symphony in four movements, where the scherzo and the adagio would have been followed by a second hymn, is a widened allegro of sonata, with exposure, development and reprise; the commentators largely agree on this subject. Similarly to the Third symphony with its two parts (Abteilungen), the scene of Faust would form a second tripartite part, corresponding to the scherzo, the adagio and the final hymn projected - but this interpretation is disputed.

By powerful chords, reinforced by the organ, the choruses intone the Latin hymn of Pentecost Veni creator spiritus. The movement thus starts with a kind of paroxysm dramatic maybe recalling the moment when Mahler was seized by the inspiration to write this work. This early medieval hymn evokes Pentecost when the Holy Spirit came upon the disciples of Jesus, but the music of Mahler does not refer in any identifiable way to the Gregorian choral.

The second part consists in the final scene of Goethe's Faust. According to the pact concluded with Mephisto, Faust should succumb to hell as of the moment when, in its perpetual aspiration to higher things, he would have reached a level where his existence satisfies him so much that he wanted the moment to last ("Oh stay! You are so beautiful!"), but the Angelic Hosts come to his rescue by the power of love.

Mahler's symphonies do not show another example for such a close musical relationship of the movements. The music of the first part frequently returns in an almost identical form in the second. Moreover, the many topics and reasons are combined in order to sound like reciprocal variations. The whole work seems to be based on a single motif never presenting itself completely.

Regarding the contents, i. e. the lyrics, the two parts seem not to have any relationship. There is, however, a bond between the hymn of Pentecost and the final scene of Faust: the divine love we already met in the finale of the Third symphony. In Mahler's thinking, Spirit, God and Love are one and the same thing. Veni, creator spiritus, infunde amorem cordibus - come, Creator Spirit, pour love in our hearts: Love is the fundamental force of human existence. Here, the bond between the final scene of Faust is to be found: the love of God leads man through purification (catharsis) to redemption and finally to his apotheosis.

So the end of the Eighth reminds the finale of the Second not only by its radiant beauty, but also by its contents: Man merges into the love of the Celestial Lord.